Mooresville, Alabama

Mooresville, Alabama | |

|---|---|

Mooresville Post Office | |

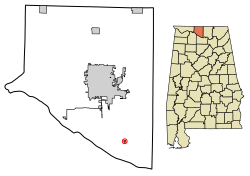

Location of Mooresville in Limestone County, Alabama. | |

| Coordinates: 34°37′37″N 86°52′52″W / 34.62694°N 86.88111°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alabama |

| County | Limestone |

| Town of Mooresville | November 16, 1818[1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.30 sq mi (0.77 km2) |

| • Land | 0.25 sq mi (0.65 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.13 km2) |

| Elevation | 577 ft (176 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 47 |

| • Density | 188.00/sq mi (72.72/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 35649 |

| Area code | 256 |

| FIPS code | 01-51264 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2406188[3] |

| Website | www |

Mooresville is a town in Limestone County, Alabama, United States, located southeast of the intersection of Interstate 565 and Interstate 65, and north of Wheeler Lake.

The town is between Huntsville and Decatur, and is part of the Huntsville-Decatur Combined Statistical Area; its population as of the 2010 census is 53, down from 59 in 2000.

Although the town's per-capita income is over $50,000, Mooresville is within the area covered by the charter for the Appalachian Regional Commission, an organization whose goal is to help increase the per-capita income of impoverished areas. Mooresville is within Corridor V of the Appalachian Development Highway System.

The town was the primary filming location for Disney's live action production of Tom and Huck (1995).[4]

The entire town, described as a picturesque early 19th century village, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[5] Many of the older public buildings, including the Stagecoach Inn and Tavern, the Brick Church, the Post Office, and the Church of Christ, are owned and maintained by the town's residents.[6]

History

[edit]Mooresville is one of the oldest incorporated towns in Alabama, having been incorporated on November 16, 1818, when Alabama was still a Territory. It was named for early settlers, George, Robert and William Moore who located on land which became the site of Mooresville.

1820s

[edit]In November of 1823, Alexander S. Thew owned a store in Mooresville.[7] In 1824, a man named Lucian Minor advertised himself as an attorney in the north Alabama area with his residence in Mooresville.[8]

On February 14, 1824, James D. Scott, a tailor and habit maker, announced that he had taken over the tailoring business formerly operated by J.L. Sloss in Mooresville, Alabama. In a public notice, he informed residents and the general public of his intention to continue the trade in all its various branches, pledging that all work entrusted to him would be neatly executed in a timely manner.[9]

On February 16, 1824, Alexander S. Thew, a merchant formerly operating in Mooresville, Alabama, announced the relocation of his business to Florence, Alabama. In a public notice published in The Democrat (Huntsville), he requested that all outstanding debts be settled immediately. Accounts owed to Thew personally were to be paid to P. Yeatman & Co., while debts to the former firm of Thew & Territt of Mooresville were to be settled with A. Vincent & Co. or J. Kenney, who occasionally visited Mooresville. Thew warned that legal action would be taken against those who failed to comply.[10]

On November 8, 1824, Richard W. Anderson & Co. announced that they would continue freighting cotton from Ditto’s Landing and other points along the river to New Orleans. The company constructed a warehouse at Dittos Landing for receiving shipments and also accepted cotton at Mooresville, Limestone County, and Isaac Lanier’s Gin on Indian Creek. The notice assured shippers that only experienced and sober boatmen would handle the transport. Early boats were planned to accommodate cotton shippers, with business coordinated through A. Vincent & Co. in Mooresville and other merchants in Huntsville and Courtland.[11]

On December 8, 1824, Dr. William McClung announced his medical practice in Mooresville, Alabama, offering his services to local residents and those in the surrounding area. He assured the public of his dedication and strict attention to all patients seeking treatment. McClung stated that he could generally be found at his shop in Mooresville, except when away on professional business.[12]

On February 1, 1825, Dr. Turner, a physician, surgeon, and midwife, announced his medical services to residents of Limestone, Madison, and surrounding counties, including Mooresville, Alabama. He planned to be available after March 1 at the Fork of the Triana, Huntsville, and Mooresville roads near Capt. Benjamin Fox’s residence. Turner published a detailed list of medical fees, including charges for travel, consultations, tooth extractions, bloodletting, and midwifery. He also offered "no cure, no pay" treatments for conditions such as gonorrhea, syphilis, cancer, and rheumatism. Additionally, he pledged to treat the poor for free.[13]

Around 1825, Andrew Johnson, later to become to 17th president of the United States, lived in Mooresville as an apprentice tailor when he was a young man.[6]

On July 15, 1825, a $10 reward was offered by James Blackwood, a resident five miles north of Mooresville, Alabama, for the capture of an enslaved man named Peter, described as a 35-year-old mulatto man, approximately six feet tall, with a thin face and Roman nose. Peter was noted to be well-dressed, carrying two broadcloth coats (one blue and one brown), a wallet, and a large butcher knife. Blackwood suspected that Peter intended to pass as a free man and escape to a free state.[14]

On January 9, 1827, Micajah Thomas, a resident six miles north of Mooresville, Alabama, placed an advertisement seeking the capture of an enslaved woman named Patsey, described as a mulatto girl well known in Huntsville and Ditto’s Landing. Thomas suspected that she was attempting to escape by boat and noted that she was intelligent and likely to disguise herself. He also described a crooked left wrist caused by a past injury.[15]

1830s

[edit]On August 3, 1830, a trust sale of enslaved individuals was announced in Mooresville, Alabama, by John Fox, Trustee, under a deed of trust executed in 1824 for the benefit of Chas King. The sale was scheduled for August 21, 1830, where numerous enslaved individuals, including men, women, and children, would be auctioned to the highest bidder for cash. The names of those to be sold included Nick, Abram, Aggy, Berry, Caty, Tom, Tempe, Maria, Dilsy, Martha, Daphna, Daniel, Caesar, James, Joe, Spencer, Sarah, Jinny, Davy, Tabby, Tom, Martha, Daphna, Daniel, Lucy, and Moses.[16]

On May 5, 1831, a trust sale of enslaved individuals was announced in Mooresville, Alabama, by Benjamin Sykes, Trustee, under a deed of trust executed in 1827 for the benefit of Charles King (deceased). The sale was scheduled for May 30, 1831, between 12 and 4 o’clock, where two enslaved individuals, Alfred and Polly, would be auctioned to the highest bidder for cash.[17]

On May 6, 1835, "Oaklands Plantation," located four miles west of Mooresville, Alabama, on the north side of the Tennessee River, was advertised for sale. The plantation spanned approximately 3,000 acres, with 1,300 acres of fertile highland and the remainder as river bottomland. At the time of the sale, 900 acres were cleared, with 600 acres planted in cotton and the remainder in corn and grain. The plantation included a gin house, overseer’s house, newly built cabins for enslaved laborers, chimneys, and stables, all described as being in excellent condition. The listing emphasized the property's prime location, being one mile from the Tennessee River and near the planned railroad terminus in Decatur. The land was owned by Thomas Bibb, with inquiries directed to James Bradley and Jas. J. Pleasants in Huntsville.[18]

On January 2, 1837, the Mooresville Female School announced the commencement of its next session on the fourth Monday of January under the superintendence of Mrs. Gay, recently from Marietta, Ohio, assisted by Mrs. Donnell. In addition to the standard curriculum, the school planned to offer instruction in the French language and music on the piano forte. The trustees emphasized the school's healthy location, affordability, and strong community support, which allowed for planned improvements and expansions over the summer. Boarding for students was available in respectable families at competitive rates compared to nearby villages.[19]

On June 15, 1838, the Mooresville Male School announced the start of its third session on the first Monday in July. The school was divided into Junior and Senior departments, offering thorough English education at the junior level and a full Classical and Scientific course at the senior level. The instructional method was compared to the Pestalozzian system, emphasizing inductive learning and parental-style governance. The school was described as being in a healthy location with a moral and steady student community. Accommodations were available for 75 students, with boarding offered at the Principal’s residence. Inquiries were directed to several community members, including Rev. Robert Donnell.[20]

1850s

[edit]On October 3, 1854, W.W. Matthews announced the auction of his estate in Mooresville, Alabama, scheduled for December 2, 1854, as he planned to move to Texas. The property consisted of 1100 acres of prime North Alabama farmland, with 500 acres in a high state of cultivation. It included a dwelling, cotton gin, horse mill, ice house, spring, and ample stock water, as well as a productive orchard. The land was described as offering excellent grazing for hogs and cattle, with access to the Memphis and Charleston Railroad, which passed through the tract.[21]

1860s

[edit]The Union Army occupied Mooresville several times during the Civil War, and a few skirmishes were fought in the vicinity. Future U.S. president James Garfield, then a Union general camped in the area, delivered a sermon at the Mooresville Church of Christ in 1863.[6] Mooresville thrived as a cotton farming hub until the early 20th century, when the boll weevil infestation wrecked the cotton economy.[22]

On September 14, 1869, reports from The Athens Post detailed an alleged insurrection plot in Mooresville, Alabama, involving a group of African Americans accused of planning an uprising against white residents. The article stated that meetings and drills had been occurring in the area, with a planned attack set for a Friday night. Local authorities and citizens were reportedly alerted by a man named Ed Lane, leading to the arrest of nine individuals, while others allegedly escaped. Three of the accused were released after "turning state's evidence," and six remained jailed awaiting trial before Judge Coman. The coverage was highly inflammatory, reflecting racial tensions during Reconstruction, and accused unnamed white individuals of inciting the alleged plot. This event underscores the climate of fear, racial unrest, and harsh legal actions against African Americans in the post-Civil War South.[23]

On September 22, 1869, reports from the Huntsville Independent described Ku Klux Klan activity and racial violence near Mooresville, Alabama. The article detailed the arrest of Bob Ice, a Black man, who allegedly informed authorities about a Black organization similar to the Evans band of Marshall. Ice claimed a meeting was planned at Bibb’s Lane, prompting the Limestone County sheriff and a group of white citizens to intervene. Five Black men were arrested, and authorities claimed they confessed to a plot to burn a local store and kill its owner and others. This led to 25 additional arrests, with all suspects taken to Athens for investigation. The report framed the event as an attempt to prevent bloodshed, but it also included politically charged accusations against Radical Republicans and Loyal Leaguers.[24]

1870s

[edit]On May 4, 1875, a report from Limestone News described labor shortages in Mooresville, Alabama, due to the departure of a large number of Black laborers from the region. In response, young white men in the area began working their own fields, demonstrating what the article called a "manly disposition" and self-reliance. The report encouraged others to follow their example rather than seeking work in overcrowded professions. This article reflects the economic and social shifts in the Reconstruction-era South, where the loss of enslaved labor and migration of Black workers forced landowners to reconsider their dependence on agricultural laborers.[25]

1880s

[edit]On January 11, 1880, The Montgomery Advertiser reported on the appointment of Luke Pryor as U.S. Senator from Alabama following the death of Senator George S. Houston. The town of Athens, Alabama, celebrated the announcement with a parade, music, and speeches, reflecting widespread local support. Pryor, who was born near Mooresville, Alabama, in 1820, was recognized for his deep ties to Limestone County, Democratic principles, and legal career. The article recounted Pryor’s early life in Mooresville, where he assisted his father by selling wood from a cart before studying law. He later became a state legislator and an attorney.[26]

On November 4, 1882, a newspaper article from The Montgomery Advertiser detailed the appointment of Luke Pryor as U.S. Senator to fill the vacancy left by the death of Senator George S. Houston. Pryor, a native of Madison County, Alabama, spent his early years in Mooresville, where his family settled after migrating from Virginia. As a child, he sold wood in the village streets to contribute to his family’s earnings before studying law and becoming an attorney. Following his appointment by Governor Cobb, Pryor received widespread support from Athens and the surrounding communities, including Mooresville. A brass band and a crowd of citizens gathered outside his home to express their congratulations. During a short speech, Pryor spoke fondly of his love for Limestone County, his political beliefs, and his dedication to public service. The event was marked by celebrations, with the town of Athens reportedly selling out of champagne. Pryor’s appointment was hailed as a triumph of democracy, as he had not actively sought the position but was instead recognized for his integrity, legal acumen, and dedication to the people. The article described him as an earnest and diligent public servant, admired for his engaging speeches, hospitality, and extensive knowledge in law, politics, and agriculture. His political philosophy was shaped by his humble beginnings in Mooresville, and he was known for his commitment to justice and civic discourse.[27]

On July 11, 1886, a newspaper article detailed the contributions of George F. Moore to the development of Mooresville, Alabama. Moore was an attorney and stockholder in the Trade Company, playing a significant role in the legal and business groundwork of local enterprises. His involvement was seen as a testament to the progressive spirit of the town, where even lawyers were shifting their focus from traditional legal work to actively engaging in business improvements. Moore was credited with establishing a thriving suburb in the southern limits of Mooresville, which was a factor in his selection as a legal advisor for the Trade Company’s corporate development. His success in this endeavor reflected the town’s growth and its increasing economic significance. Born in Talladega, Alabama, on August 9, 1849, Moore was educated at the University of Virginia, where he studied both general academics and law. He began practicing law in Rockford in 1872 before moving to Montgomery in 1874, where he built a prominent legal and political career. In 1884, he ran for Attorney General of Alabama, further cementing his influence in the state. In addition to his legal work, Moore helped organize the Alabama Loan and Investment Company, serving as its president. He was one of the first Masons in Alabama to achieve the 33rd degree, signifying his deep involvement in civic and fraternal organizations. Known as a progressive leader, Moore was actively shaping the business landscape of the region. Moore was married to Miss Merrill of Columbus, Mississippi, and had recently moved into a new, stylish home at the corner of Scott and Decatur streets.[28]

Historic buildings

[edit]- Stagecoach Inn and Tavern (1820s) – a frame building constructed before 1825 that served as an inn and post office. This building was documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey in the 1930s, and underwent extensive restoration in the 1990s.[6]

- Mooresville Post Office (1840) – located at the corner of Lauderdale and High streets, this post office is the oldest in operation in Alabama and has call boxes dating before the American Civil War. Some of the call boxes have been owned by the same families since before the Civil War. The call boxes and some of the office furnishings actually predate the building, having been used in the nearby Stagecoach Inn and Tavern.[6]

- Brick Church (1839) – a Greek Revival-style church built of handmade bricks that stands on Lauderdale Street. Originally a Presbyterian church, it later served as a Methodist church and a Baptist mission. The church's recessed entrance is supported by two stucco-covered columns.[6]

- Mooresville Church of Christ (1854) – a white clapboard church on Market Street that originally served as a meeting house for the Disciples of Christ. The rear wing and entry vestibule were added in 1937.[6]

Geography

[edit]

Mooresville is located at 34°37′37″N 86°52′52″W / 34.62694°N 86.88111°W (34.626931, -86.881091).[29] The town lies southwest of Huntsville and northeast of Decatur in southern Limestone County. Wheeler Lake, an artificial reservoir along the Tennessee River, lies to the south.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 0.1 square miles (0.26 km2), all land.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 165 | — | |

| 1880 | 183 | 10.9% | |

| 1890 | 143 | −21.9% | |

| 1900 | 150 | 4.9% | |

| 1910 | 137 | −8.7% | |

| 1920 | 144 | 5.1% | |

| 1930 | 114 | −20.8% | |

| 1940 | 129 | 13.2% | |

| 1950 | 101 | −21.7% | |

| 1960 | 93 | −7.9% | |

| 1970 | 72 | −22.6% | |

| 1980 | 58 | −19.4% | |

| 1990 | 54 | −6.9% | |

| 2000 | 59 | 9.3% | |

| 2010 | 53 | −10.2% | |

| 2020 | 47 | −11.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[30] | |||

As of the census[31] of 2000, 59 people, 24 households, and 19 families resided in the town. The population density was 741.1 inhabitants per square mile (286.1/km2). There were 28 housing units at an average density of 351.7 per square mile (135.8/km2). The racial makeup was 88.14% White and 11.86% Black or African American.

There were 24 households, of which 25.0% had children under 18 living with them; 66.7% were married couples living together; 12.5% had a female householder with no husband present; and 20.8% were non-families. 20.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 2.84.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 16.9% under the age of 18, 6.8% from 18 to 24, 20.3% from 25 to 44, 40.7% from 45 to 64, and 15.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 50 years. For every 100 females, there were 118.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 104.2 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $54,167, and the median income for a family was $136,039. Males had a median income of $51,667 versus $65,417 for females. The per capita income for the town was $51,694, unusually high for the state. No families and 4.3% of the population are living below the poverty line, including 3.33% of those over 64.

Education

[edit]It is in the Limestone County School District.[32]

Notable people

[edit]- Wade Keyes, Confederate States Attorney General in 1861, and from 1863 to 1864

- James Sloss, planter, industrialist, and founder of Sloss Furnaces

Gallery

[edit]-

Old Brick Church in Mooresville

-

Pews in Old Brick Church

References

[edit]- ^ A Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama: Containing The Statutes and Resolutions in Force at the end of the General Assembly in January, 1823. Published by Ginn & Curtis, J. & J. Harper, Printers, New-York, 1828. Title 62. Chapter XXIV. Page 802-803. "An Act to Incorporate the Town of Mooresville, and for other purposes.—Passed November 16, 1818." (Google Books)

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Mooresville, Alabama

- ^ "Mooresville". Decatur Morgan County Tourism. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Town of Mooresville website

- ^ "Notice, The Firm of Thew & Sterritt, Merchants". The Democrat. November 25, 1823. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Lucian Minor, Attorney at Law". The Democrat. March 2, 1824. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Tailor & Habit Maker". The Democrat. February 14, 1824. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Removal". The Democrat. March 9, 1824. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Cotton Freighting". The Democrat. November 8, 1824. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Dr. William McClung". The Democrat. December 28, 1824. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Doct. Turner". The Democrat. April 5, 1825. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "$10 Reward". The Democrat. July 19, 1825. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Runaway". The Democrat. January 19, 1827. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Trust Sale of Negroes". The Democrat. August 19, 1830. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Trust Sale". The Democrat. June 30, 1831. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Oaklands for Sale". The Democrat. May 6, 1835. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Mooresville Female School". The Democrat. January 31, 1837. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Education". The Democrat. June 30, 1838. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Valuable Real Estate at Auction". The Democrat. November 30, 1854. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ James P. Kaetz, "Mooresville," Encyclopedia of Alabama, 31 August 2016.

- ^ "Attempted Insurrection". The Montgomery Advertiser. September 14, 1869. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Ku Klux Developments". The West Alabamian. September 22, 1869. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ The Montgomery Advertiser. May 4, 1875. p. 1 https://www.newspapers.com/image/355632108/?match=1&clipping_id=new. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "The Enthusiasm in Athens Over the Appointment of Senator Pryor". The Montgomery Advertiser. January 11, 1880. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Hon. Luke Pryor". The Montgomery Advertiser. November 4, 1882. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "Geo. F. Moore". The Montgomery Advertiser. July 11, 1886. p. 1. Retrieved March 18, 2025.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Limestone County, AL" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 1, 2022. - Text list

External links

[edit]- Town website

- Mooresville: A Town of Charm & History Archived 2015-09-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Towns in Limestone County, Alabama

- Populated places established in 1818

- Huntsville-Decatur, AL Combined Statistical Area

- National Register of Historic Places in Limestone County, Alabama

- Historic districts in Limestone County, Alabama

- Alabama populated places on the Tennessee River

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in Alabama