Maravi

Kingdom of Maravi malaŵí (Chichewa) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1480–1891 | |||||||||||

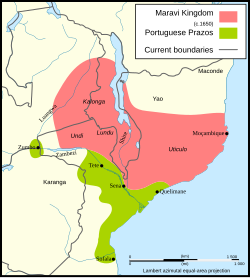

The Maravi Kingdom at its greatest extent in the 17th century. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Manthimba, Mankhamba | ||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | c. 1480 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1891 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

Maravi was a kingdom which straddled the current borders of Malawi, Mozambique, and Zambia, in the 16th century. The present-day name "Maláŵi" is said to derive from the Chewa word malaŵí, which means "flames". "Maravi" is a general name of the peoples of Malawi, eastern Zambia, and northeastern Mozambique. The Chewa language, which is also referred to as Nyanja, Chinyanja or Chichewa, and is spoken in southern and central Malawi, in Zambia and to some extent in Mozambique, is the main language that emerged from this empire.

The Maravi Confederacy was founded by Bantu people immigrating into the valley of the Shire River (flowing out of Lake Nyassa) around 1480 AD. It prospered into the late 18th century, extending to reach what is now belonging to Zambia and Mozambique.

At its greatest extent, the state included territory from the Tonga and Tumbuka people's areas in the north to the Lower Shire in the south, and as far west as the Luangwa and Zambezi river valleys. Maravi's rulers belonged to the Mwale matriclan and held the title Kalonga. They ruled from Manthimba, the secular/administrative capital, and were the driving force behind the state's establishment. Meanwhile, the patrilineal Banda clan, which traditionally provided healers, sages and metallurgists, took care of religious affairs from their capital Mankhamba near Ntakataka.

Name

[edit]The name Maravi is a Portuguese derivation on the word Malawi, which the Chewa had used to refer to themselves.[1]: 1 In Chichewa, malaŵí means "flames".[2][3] According to Samuel Josia Ntara's Mbiri ya Achewa (1944/5), "Malawi" referred to an area along Lake Malawi where a Chewa king and his people settled long ago.[1]: 15 Chewa tradition says when they first saw Lake Malawi from the highlands, it looked like a mirage or flames. Subsequently, the land between Lake Malombe and the Linthipe River was called Malawi, and they referred to themselves as Amalawi.[4]: 39

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]The Chewa have two competing traditions of origin. The first holds that Chiuta (God) created the Chewa and animals at Kaphirintiwa Hill, where there are patterns of seemingly human and animal footprints in the rock. Thus it holds that the Chewa have always inhabited their present homeland.[4]: 40–41

The second is in agreement with the most widely accepted models of the Bantu expansion, where most Chewa traditions hold that they migrated from Uluwa or Luba in Katanga, DR Congo, through modern-day Zambia to modern-day Malawi, and they are associated with Naviundu pottery in Katanga dated to the 4th century.[5]: 22, 32 They trace the origins of their clan names to this final migration, however due to how fundamental clans are to Chewa society this seems unlikely. Scholars consider the Banda clan and other smaller clans to have arrived in Malawi first, and the Phiri clan to have migrated later. They use the name "Maravi" to refer to the Phiri, and "pre-Maravi" to refer to the Banda and others.[4]: 37–39

According to tradition, when the Chewa reached Malawi, they found a pygmy people (called Akafula, Abatwa, or Amwandionerakuti) who they fought a battle against (near Mankhamba) and drove south across the Zambezi River.[4]: 43

Beginning as early as the thirteenth century, the first signs of a large-scale migration of related clans entered the region of Lake Malawi. Traditional accounts indicate that these people originated in the Congo Basin to the west of Lake Mweru, in an area that subsequently formed part of the Luba Kingdom. The movement continued during the succeeding two or three centuries, but it appears certain that by the sixteenth century the main body of these people, known collectively as the Maravi, were settled in the Shire River valley and over a wide area lying generally west and southwest of Lake Malawi, including parts of present-day Zambia and Mozambique.

Apogee

[edit]After contact with the Portuguese, trade intensified. It included such items as beads of the Khami type and Chinese porcelain imported via Portuguese intermediaries. The first (colonial) historical account of the Maravi was by Gaspar Bocarro, a Portuguese man who traveled through their territory in 1616.[6] The picture presented in the 1660s by Father Manuel Barretto, a Jesuit priest, was of a strong, economically active confederation that swept an area from the coast of Mozambique between the Zambezi River and the bay of Quelimane for several hundred kilometres into the mainland. An account from the following century implied that the western limits of the confederation were near the Luangwa River and that it extended on the north to the Dwangwa River.[7]

Decline

[edit]In the 18th and 19th centuries, the state declined as many clans grew more autonomous.[8] Maravi was invaded by Ngoni people fleeing the Mfecane[9] and was frequently raided by the neighboring Yao people (East Africa), selling captive Maravi on the slave markets of Kilwa and Zanzibar. In the 1860s, Islam was introduced into the region through contact with Swahili slave traders. The region was visited by David Livingstone and stations were set up by Protestant missionaries in 1873. A British consul was also sent there in 1883. David Livingstone visited Lake Nyasa in 1859, and other Protestant missionaries soon followed.

Government

[edit]The state was headed by a Kalonga (king/queen), and other titles included Nyangu (reserved for either the Kalonga's mother or sister) and Mwali (the Kalonga's main wife). As a matrilocal society, Nyangu was head of the Phiri clan. Makewana or Mangadzi was a female priestess and rainmaker, and also head of the Banda clan.[4]: 38

References

[edit]- ^ a b Juwayeyi, Yusuf M. (2020). "Introduction". Archaeology and Oral Tradition in Malawi: Origins and Early History of the Chewa. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84701-253-1.

- ^ Conroy, Anne (2006), Conroy, Anne C.; Blackie, Malcolm J.; Whiteside, Alan; Malewezi, Justin C. (eds.), "The History of Development and Crisis in Malawi", Poverty, AIDS and Hunger: Breaking the Poverty Trap in Malawi, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 14–32, doi:10.1057/9780230627703_2, ISBN 978-0-230-62770-3, retrieved 2025-03-10

- ^ Mkandawire, Bonaventure (2010). "Ethnicity, Language, and Cultural Violence: Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda's Malawi, 1964-1994". The Society of Malawi Journal. 63 (1): 23–42. ISSN 0037-993X.

- ^ a b c d e Juwayeyi, Yusuf M. (2020). "The origins and migrations of the Chewa according to their oral traditions". Archaeology and Oral Tradition in Malawi: Origins and Early History of the Chewa. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84701-253-1.

- ^ Juwayeyi, Yusuf M. (2020). "The Bantu origins of the Chewa". Archaeology and Oral Tradition in Malawi: Origins and Early History of the Chewa. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84701-253-1.

- ^ Huhn, Arianna. "History".

- ^ "Maravi Confederacy | historical empire, Africa | Britannica".

- ^ "Maravi Confederacy | historical empire, Africa | Britannica".

- ^ "Axis Gallery". Archived from the original on 2006-01-09.

https://axis.gallery/exhibitions/nyau-masks/