Corvus (boarding device)

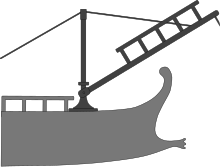

The corvus (Latin for "crow" or "raven") was a Roman ship mounted boarding ramp or drawbridge for naval boarding, first introduced during the First Punic War in sea battles against Carthage. It could swivel from side to side and was equipped with a beak-like iron hook at the far end of the bridge, from which the name is figuratively derived, intended to anchor the enemy ship.

The corvus was still used during the last years of the Republic. Appian mentions it being used on August 11th 36BC, during the battle of Mylae, by Octavian's navy led by Marcus Agrippa against the navy of Sextus Pompeius led by Papias.[citation needed]

Technical description

[edit]In Chapters 1.22–4.11 of his History, Polybius describes the device as a bridge 1.2 m (4 ft) wide and 10.9 m (36 ft) long, with a small parapet on both sides. The engine was probably mounted at the prow of the ship, where a pole and a system of pulleys allowed the bridge to be raised and lowered. A heavy spike, shaped like a bird’s beak, was affixed to the underside of the device, designed to pierce and anchor into an enemy ship’s deck when the boarding bridge was dropped. This secured the vessels together and provided a stable route for Roman legionaries—serving as specialized naval infantry known as marinus—to board and capture the enemy ship.

Strategic context and advantages

[edit]In the 3rd century BCE, Rome was not a naval power and had little experience in sea combat. Before the First Punic War began in 264 BCE, the Roman Republic had not campaigned outside the Italian Peninsula. The Republic's military strength was in land-based warfare, and its main assets were the discipline and courage of the Roman soldiers. This background supports the view of the ancient historian Polybius, who presents the Romans as inexperienced at sea. According to this interpretation, the boarding bridge, known as the corvus, was crucial to their early naval success because it allowed them to turn sea battles into land-based warfare. In such situations, Roman training could give them the upper hand.[1]

However, Steinby questions how decisive the corvus really was. She notes that Rome won several battles without it, including their first major victory on the way to Sicily, during which many Punic ships were captured. She also points out that the corvus is only mentioned twice in the surviving sources: at the battles of Mylae (260 BCE) and Ecnomus (256 BCE). After that, it disappears from the historical record.[1]

The device was certainly useful, especially close to the shore at Ecnomus, but it was not the only factor in Rome’s success. The way the Roman fleet was arranged during that battle shows a high level of confidence and a clear plan to move towards Africa. The boldness of that expedition, carried out by a navy that was only a few years old, suggests that the corvus was not just a way to deal with Carthaginian strength at sea. It was likely part of a wider and more organised strategy shaped by ambition and growing skill.[2]

Despite Polybius’ view, Roman actions in the early years of the war suggest they were not simply figuring things out as they went. In 259 BCE, Lucius Cornelius Scipio led a successful campaign in Sardinia and Corsica. In 258 they won at Sulci, and in 257 they launched attacks on Malta and the Lipari Islands, ending with a Carthaginian retreat at Tyndaris. These operations show Rome’s increasing confidence at sea and challenge the idea that the corvus was only a defensive tool. Instead, it seems to have been one element in a much broader naval policy.[2]

Usage

[edit]The corvus is only clearly mentioned in ancient sources during two battles in the First Punic War: Mylae in 260 BCE and Ecnomus in 256 BCE. There is no direct evidence that it was used in any other engagements, and it disappears from the historical record after this point. Its limited appearance suggests that the corvus was not a permanent part of Roman naval tactics, but more likely a short-term solution suited to the early phase of Rome’s development at sea.[1]

The fact that it was not used again may suggest that it was designed to meet a specific tactical need, especially when Roman crews were still inexperienced and relied heavily on land-based fighting techniques. As their skills at sea improved, the advantages of boarding using the corvus may have become less important. It is also possible that the Carthaginians found ways to counter it or avoid close combat altogether, which would have made the device less useful in practice.[1]

The Battle of Mylae in 260 BCE was Rome's first major naval victory during the First Punic War. It highlighted the successful use of the corvus, a boarding device designed to take advantage of Roman infantry tactics at sea. According to Polybius, when Roman consul Gaius Duilius learned that Carthaginian forces were attacking the area around Mylae, he took command of the fleet and sailed out to meet them. The Carthaginians, confident in their naval superiority, advanced without keeping proper formation. As the battle began, the Romans used the corvus to board enemy ships and fight hand-to-hand, where their training on land gave them the advantage. This tactic led to the capture of thirty Carthaginian ships, including the flagship of their commander, Hannibal, who narrowly escaped. Seeing how effective the corvus was, the rest of the Carthaginian fleet tried to avoid direct combat by outmanoeuvring the Romans. However, they were stopped by the flexibility of the device and the surprising skill of the Roman crews. In the end, the Carthaginian fleet retreated, losing fifty ships in total.[3]

The Battle of Ecnomus in 256 BCE was a major naval clash during the First Punic War, fought between the Roman Republic and Carthage off the southern coast of Sicily. As the Romans prepared to move their army to North Africa, the Carthaginians attempted to stop them with a fleet arranged to surround the Roman formation. The fighting broke out across a wide area and developed into three separate engagements. The Carthaginians used their faster ships to try flanking movements, while the Romans, led by the consuls Marcus Atilius Regulus and Lucius Manlius Vulso, focused on close combat. They used boarding devices known as corvi (or "ravens") to grapple with enemy ships and fight hand-to-hand. Roman squadrons supported each other well, and this coordination helped them defeat their opponents, either capturing or sinking a large number of Carthaginian vessels. Polybius notes that the Carthaginians were reluctant to fight at close range, likely due to fear of the corvus, which had already shown its worth at Mylae. In the end, the Romans achieved a clear victory. Carthage lost over thirty ships sunk and sixty-four captured, while the Romans lost twenty-four. After the battle, the Roman fleet crossed to North Africa and landed at the city of Aspis, which they quickly secured. They plundered the surrounding area before the consuls divided their tasks: Regulus stayed in Africa with the army, while Vulso sailed back to Rome with the fleet and the prisoners. The scale and organisation of the expedition, along with Rome’s ability to adapt its tactics, showed a new level of confidence at sea and marked one of the high points of Roman naval efforts during the war.[4]

Limitations and decline

[edit]Despite its advantages, the boarding bridge had a serious drawback: it could not be used in rough seas. The rigid connection between two bobbing ships posed a serious risk to their structural integrity. Under such conditions, the corvus became useless as a tactical weapon.[5] The added weight on the prow may also have compromised the ship's manoeuvrability, and it has been suggested that this instability contributed to the loss of almost two entire Roman fleets during storms in 255 BCE and at the Drepana in 249 BCE.[5] These losses may have encouraged Rome to abandon the device in later ship designs.

However, other analyses dispute the idea that the corvus significantly affected stability. J.W. Bonebakker, former Professor of Naval Architecture at TU Delft, estimated the bridge’s weight at one ton and concluded that “it is most probable that the stability of a quinquereme with a displacement of about 250 m3 (330 cu yd) would not be seriously upset” when the bridge was raised.[5]

This view has led some historians to argue that the corvus may not have been as essential or revolutionary as Polybius suggests. The first Roman fleet, built rapidly from unseasoned timber, was heavy and slow, making a boarding bridge a practical solution to compensate for poor manoeuvrability. While effective for a time, Roman naval tactics and strategy did not depend solely on the device. Rather than being a decisive instrument, the corvus functioned as one tool among many in an increasingly capable navy operating under a broader strategic vision—emphasizing coordination, long-term maritime development, adaptability, and the integration of land-based military strengths.[6]

Regardless of the cause, Rome appears to have abandoned the corvus by the end of the First Punic War. As Roman crews gained experience, naval tactics improved, reducing the device’s relative utility. It is not mentioned in historical sources after the Battle of Ecnomus, and the decisive Battle of the Aegates Islands in 241 BCE was apparently won without it. By 36 BCE, during the Battle of Naulochus, the Roman navy was using a different boarding system: the harpax, a harpoon-and-winch mechanism.

Modern interpretations

[edit]The design of the corvus has undergone many transformations throughout history. The earliest suggested modern interpretation of the corvus came in 1649 by German classicist Johann Freinsheim. Freinsheim suggested that the bridge consisted of two parts, one section measuring 24 ft (7.3 m) and the second being 12 ft (3.7 m) long. The 24 ft (7.3 m) section was placed along the prow mast and a hinge connected the smaller 12 ft (3.7 m) piece to the mast at the top. The smaller piece would have been the actual gangway as it could swing up and down, and the pestle was attached to the end.[7]

The classical scholar and German statesman B.G. Niebuhr ventured to improve the interpretation of the corvus and proposed that the two parts of Freinsheim’s corvus simply needed to be swapped. By applying the 12 ft (3.7 m) side along the prow mast, the 24 ft (7.3 m) side could be lowered onto an enemy ship by means of the pulley.[8]

The German scholar K.F. Haltaus hypothesized that the corvus was a 36 ft (11 m) long bridge with the near end braced against the mast via a small oblong notch in the near end that extended 12 ft (3.7 m) into the bridge. Haltaus suggested that a lever through the prow mast would have allowed the crew to turn the corvus by turning the mast. A pulley was placed on the top of a 24 ft (7.3 m) mast that raised the bridge in order to use the device.[9]

The German classical scholar Wilhelm Ihne proposed another version of corvus that resembled Freinsheim’s crane with adjustments in the lengths of the sections of the bridge. His design placed the corvus twelve feet above the deck and had the corvus extend out from the mast a full 36 ft (11 m) with the base of the near end connected to the mast. The marines on deck would then be forced to climb a 12 ft (3.7 m) ladder to access to the corvus.[10]

The French scholar Émile de St. Denis suggested the corvus featured a 36 ft (11 m) bridge with the mast hole set 12 ft (3.7 m) from the near end. The design suggested by de St. Denis, however, did not include an oblong hole and forced the bridge to travel up and down the mast completely perpendicular to the deck at all times.[11]

The next step in that direction occurred in 1956, when the historian H.T. Wallinga published his dissertation The Boarding-Bridge of the Romans. It suggested a different full-beam design for the corvus, which became the most widely accepted model among scholars for the rest of the twentieth century. Wallinga's design included the oblong notch in the deck of the bridge to allow it to rise at an angle by the pulley mounted on the top of the mast.[12]

Revisionist debate

[edit]Not all scholars have accepted the idea that the Romans invented and used the corvus as a specialized boarding device. In 1907, the historian William W. Tarn argued that the corvus never existed as described in ancient sources.[13]

Tarn believed that the bridge's weight would have destabilized Roman ships, which were not designed to carry such equipment. He proposed that when the corvus was raised, it would shift the center of gravity so dramatically that the vessel would capsize.[14] Instead, Tarn suggested the corvus was likely an enhanced version of the grapnel pole—a simpler boarding device used in Greek naval warfare as early as 413 BCE.[15]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Christa Steinby, Rome versus Carthage: The War at Sea (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Maritime, 2014), p. 68.

- ^ a b Christa Steinby, The Roman Republican Navy: From the Sixth Century to 167 B.C. Commentationes Humanarum Litterarum 123 (Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica, 2007), p. 95.

- ^ Polybius, The Histories, 1.22.

- ^ Polybius, The Histories, 1.25–1.29.

- ^ a b c Herman Tammo Wallinga, The Boarding-Bridge of the Romans: Its Construction and Its Function in the Naval Tactics of the First Punic War (Groningen and Djakarta: J.B. Wolters, 1956), pp. 77–90.

- ^ Christa Steinby, The Roman Republican Navy: From the Sixth Century to 167 B.C. Commentationes Humanarum Litterarum 123 (Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica, 2007), p. 104.

- ^ Freinsheim, Johann (1815). The History of Titus Livius with the entire Supplement of Johann Freinsheim Volume II. London: W. Green & T. Chaplin. pp. 216–217.

- ^ Niebuhr, B. (1851). The History of Rome, Volume III. London: Taylor, Walton, and Maberly. p. 578.

- ^ Wallingha, Herman (1956). "The Boarding Bridge of the Romans". J. B. Wolters. p. 12.

- ^ Ihne, William (1871). The History of Rome. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 57.

- ^ de St. Denis, Emile (1946). "Une machine de guerre maritime: le corbeau de Duilius". Latomus. 5 (3/4): 359–367. JSTOR 41516556.

- ^ Wallinga, Herman (1956). The Boarding Bridge of the Romans. J. B. Wolters. pp. 19–25.

- ^ Tarn, W. (1907). "Fleets of the First Punic War". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 27: 48–61. doi:10.2307/624404. JSTOR 624404.

- ^ Tarn, W. (1930). Hellenistic Military & Naval Developments. Cambridge University Press. p. 149.

- ^ Tarn, W. (1910). A Companion to Latin Studies. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 490.

References

[edit]- Wallinga, Herman Tammo (1956). The boarding-bridge of the Romans: its construction and its function in the naval tactics of the first Punic War. Groningen and Djakarta, J.B. Wolters.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2004). The Fall of Carthage. London, Cassel Publications. ISBN 0-304-36642-0.

- Gonick, Larry (1994). The Cartoon History of the Universe II: From the Springtime of China to the Fall of Rome. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-26520-4.

- Steinby, Christa (2014). Rome versus Carthage: The War at Sea. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Maritime.

- Steinby, Christa (2007). The Roman Republican Navy: From the Sixth Century to 167 B.C. Commentationes Humanarum Litterarum 123. Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica.

- Polybius (c. 2nd century BCE). The Histories, Book 1. Translated by Evelyn S. Shuckburgh. London: Macmillan, 1889. Online version at LacusCurtius.

- de St. Denis, Emile (1946). "Une machine de guerre maritime: le corbeau de Duilius". Latomus. 5 (3/4): 359–367. JSTOR 41516556.

- Freinsheim, Johann (1815). The History of Titus Livius with the entire Supplement of Johann Freinsheim, Volume II. London: W. Green & T. Chaplin. pp. 216–217.

- Ihne, William (1871). The History of Rome. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 57.

- Niebuhr, B. (1851). The History of Rome, Volume III. London: Taylor, Walton, and Maberly. p. 578.

- Tarn, W. (1907). "Fleets of the First Punic War". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 27. doi:10.2307/624404. JSTOR 624404.

- Tarn, W. (1910). A Companion to Latin Studies. London: Cambridge University Press. p. 490.

- Tarn, W. (1930). Hellenistic Military & Naval Developments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 149.

- Wallinga, Herman (1956). The Boarding-Bridge of the Romans: Its Construction and Its Function in the Naval Tactics of the First Punic War. Groningen and Djakarta: J. B. Wolters. pp. 12, 19–25, 77–90.